Lather, rinse, repeat

Routine student-teacher communication during pandemic imperative to academic success

It’s a paradoxical thought, but the sources of our anxieties are oddly integral to our lifestyles. That’s the enigma of public education, at least from a student’s perspective.

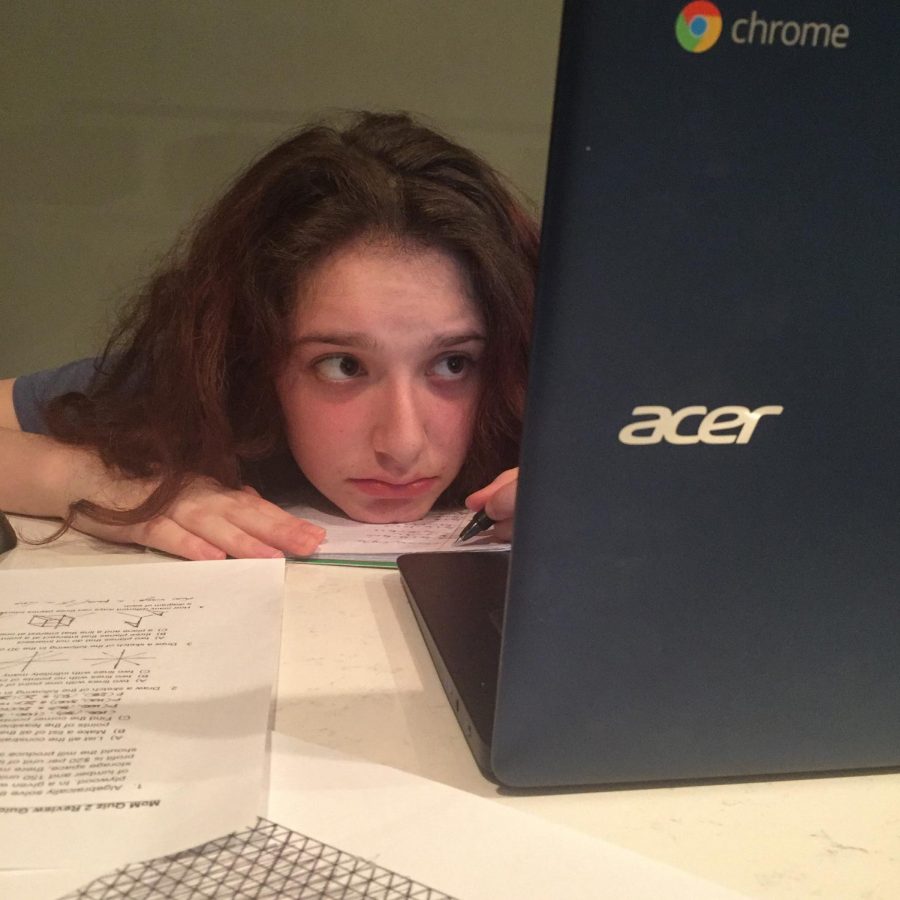

Like many kids coping with the outbreak of COVID-19 and associated social restrictions, I, too, have lapsed into the all-too-addictive binge cycle of sleeping, eating, and watching TV. Amidst parents’ returns from frenzied grocery runs, mass quantities of junk food in hand, Netflix has never been so exhausted by streaming activity. As physical exercise decreases, teenagers spend exponentially more time on phones, tablets, and computers and, incidentally, experience bouts of fatigue stemming from a collective yearning to avoid all forms of mental engagement. This behavior is cyclical and, though presently idealistic, can be counterproductive to maintaining established goals.

Thus far, the remote learning agenda laid out by CPS has far underwhelmed students’ expectations for continuous content learning, with virtual curriculum few-and-far-between and no equitable measures at present to enforce its completion. As a result of Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) guidelines making all schoolwork optional, many students have lost interest in endeavors to which they once aspired when influxes of grades served as a motivator. Educators need to make a demonstrably more conscious and involved effort to interact with their students and equip them with the resources necessary to continue progressing on a successful academic pathway.

Teenagers, by nature, are creatures of habit. They’re adaptable when need be but inherently gravitate toward the path of least resistance when given the option. Would I rather log onto Khan Academy of my own accord or watch the entirety of the Tiger King documentary, consuming an entire vat of ice cream, all in one sitting? There’s little need for debate.

However, with a lack of both motivation within students and little guidance from teachers, students’ academic capacities are being shortchanged. This reality is especially relevant for those enrolled in schools like Jones, for they have been conditioned not only to rationalize but embrace their quintessentially hyper-competitive, pseudo-energetic atmospheres. Jones students, in particular, are regularly pushed to work to their breaking points; now, as students suffer from instructional relapse, they become mentally detached, cultivating a reality harsher, still, when they sit for exams – namely Advanced Placement (AP) and SAT/ACT – in the coming months. It’s almost inevitable that test scores will plummet due to large-scale reduction in material absorption and teachers scrambling to compensate for missed content.

Though they may not like to admit it, students crave structure, a critical component suddenly absent from their daily routines. As remote learning begins, it is the obligation of educators, just as they would do in traditional leadership settings, to provide inclined students with the structure and direction to which they are entitled.

So, even as classroom instruction is no longer feasible, how can students and teachers make the most of remote learning? Video conferencing, an increasingly popular networking module, can be used to maximize interactivity and bridge contact between both parties. Via bases like Zoom, Skype, and various Google platforms, up to 100 participants can converse freely with audio and video functions that can be muted and disabled, respectively, at individual discretion. Speaking from personal experience, video conferencing has proven effective as my peers and I have interacted with my history teacher on several occasions over Google Hangouts. Considering the copious content covered in rigorous curriculums like those offered at Jones, optimum instructional time is vital to successful academic performance.

And, while affordable access to necessary technology is not a viable option for many students, CPS has aimed to lessen device disparity by making Chromebooks available for pick-up at various schools throughout the city. As of now, however, fewer than 100 Chromebooks have been checked out in a Jones student body of 1,861, a statistic that questions the absolute need for the widespread allocation of school-subsidized technology. If the need – or interest, for that matter – doesn’t appear great, what’s to prevent teachers from conducting lectures on a platform that appeals to the vast majority of students? Furthermore, work is not strictly confined to Chromebooks and can be accessed through any device or medium available at home, including phones and tablets.

To those well-intentioned, yet indifferent: it doesn’t suffice to check in with a cursory greeting or general phrase of encouragement. As the nationwide closing of schools for the remainder of the academic year – and possibly longer – has come to fruition, it’s now critical to facilitate a sustainable educational foundation to ensure that students are prepared to re-engage when these extenuating circumstances are alleviated.

In time, schools will reopen, and students and teachers will be confronted with a new normal. It’s going to take a collective, comprehensive effort to define, navigate, and, ultimately, normalize this new normal. It’s only fair that everyone plays their part.